- Aircrew

- Operational Suitability Data (OSD) for flight crew (FC)

- Licensing

- Upset Prevention and Recovery Training

- Performance-based Navigation applicability

- Cabin Crew

- Definition of ‘cabin crew’

- Medical fitness

- Practical ‘raft’ training

- Instructor and Examiner being the same person – conflict of interest

- Cabin Crew Attestation

- Fire and smoke training

- Language proficiency

- Aircraft type training

- Reduction of cabin crew during ground operations

- Minimum required cabin crew

- Working for multiple operators

- Medical

- Flight Simulation Training Devices (FSTDs)

- General

- Continuing Airworthiness

- Air Operations

- Level of Involvement (LOI)

- Airspace Usage requirements

- Third Country Operators (TCO)

- Initial Airworthiness

- Additional Airworthiness specifications

- Basic Regulation

- ATCO Licensing

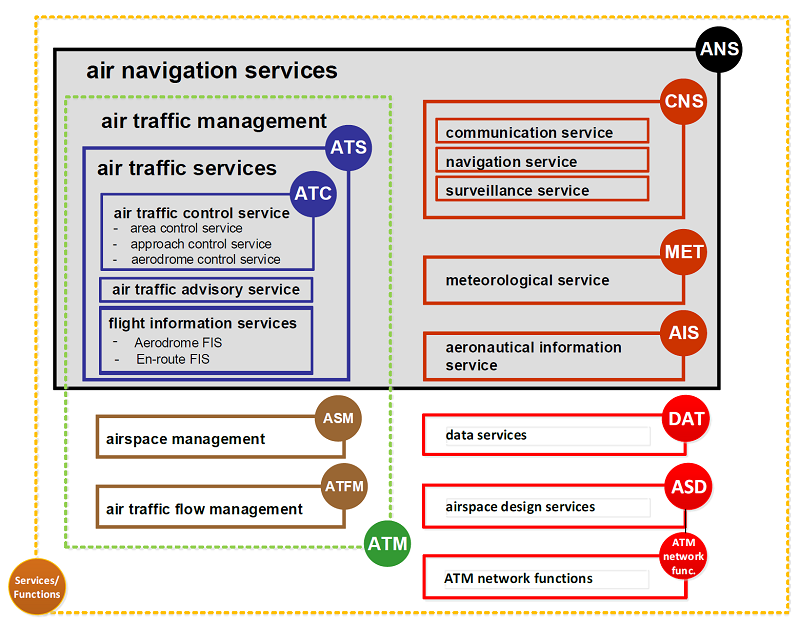

- Air Traffic Management (ATM) / Air Navigation Services (ANS)

- Air Traffic Management / Air Navigation Services (ATM/ANS) ground equipment

- Application for DPO

- Classification or notification of changes

- Acceptance of approvals issued by third countries

- Categorisation of systems or equipment

- Categorisation of software

- Commercial off the shelf (COTS) systems or equipment

- Cloud-based architectures

- Development Assurance for Software or Hardware

- Non-compliance

- Partnership Agreements

- Registry of certificates, statements of compliance, defects

- Scope/Applicability

- Means of compliance (MOC)

- Conformity assessment during the transition period

- Implementation support to stakeholders

- Aerodromes (ADR)

- Drones (UAS)

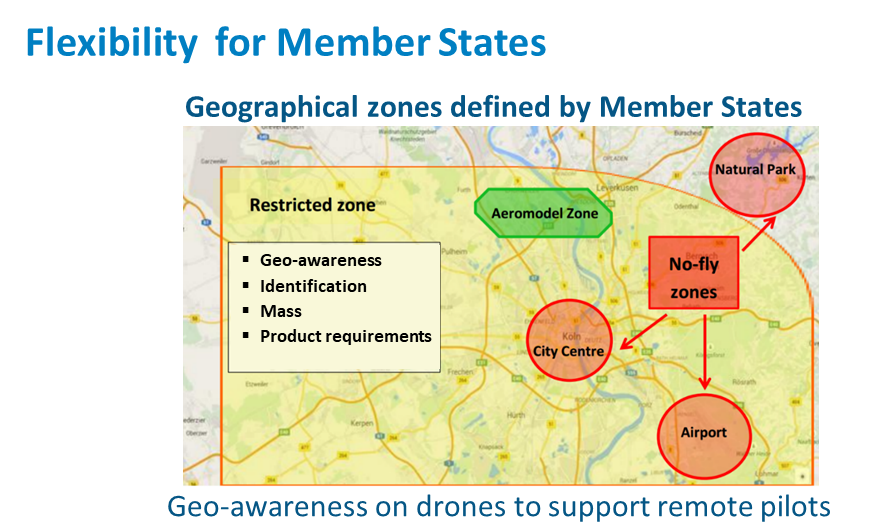

- Provisions applicable to both ‘open’ and ’specific’ category

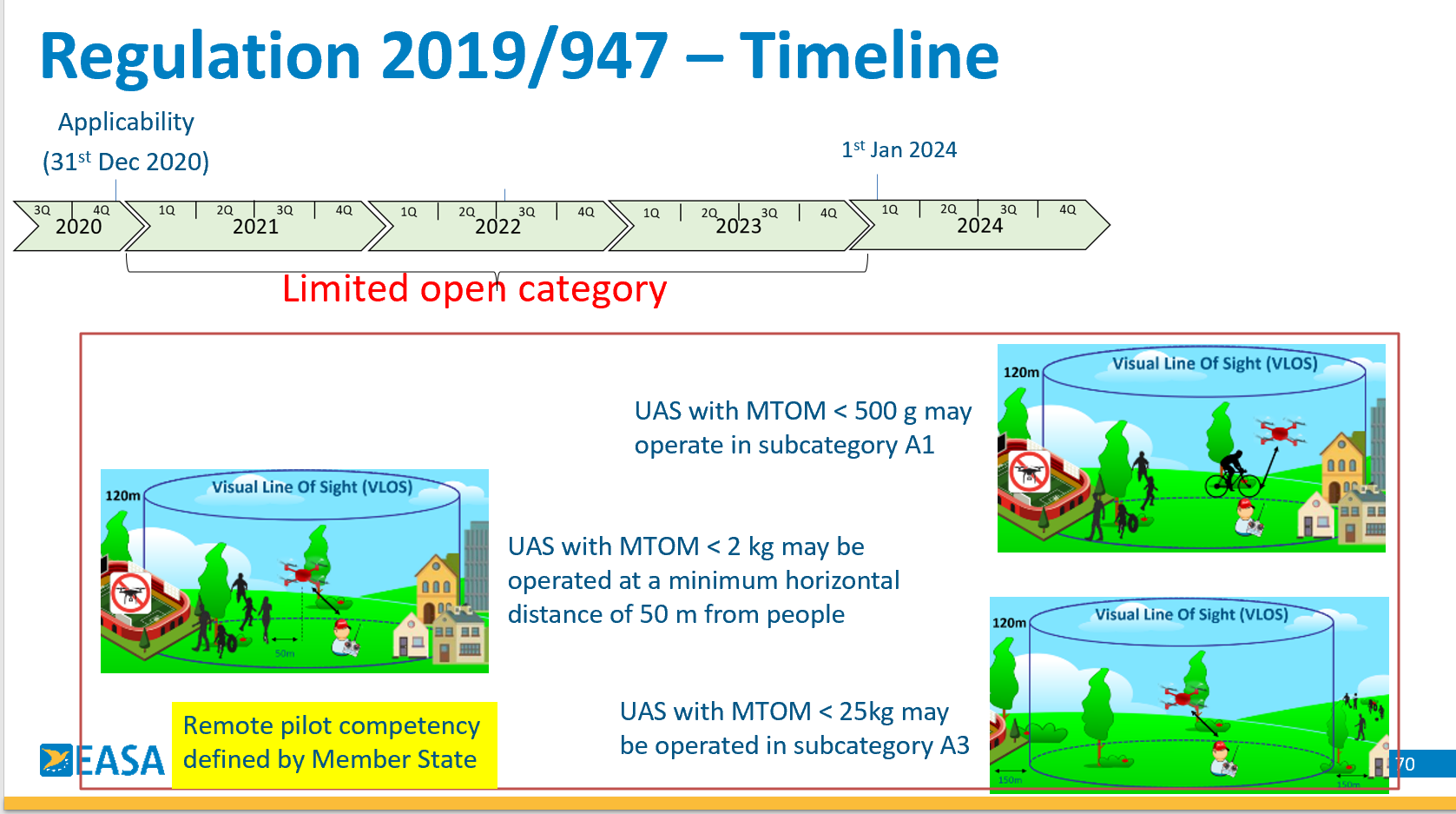

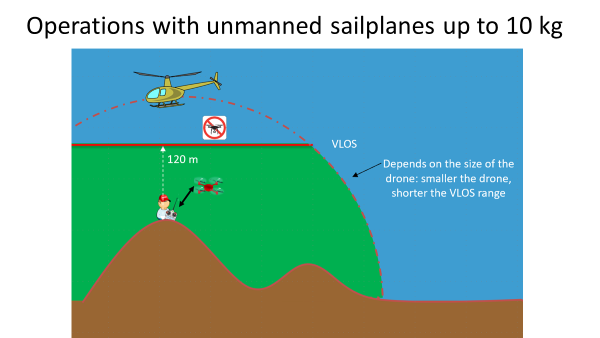

- Open category

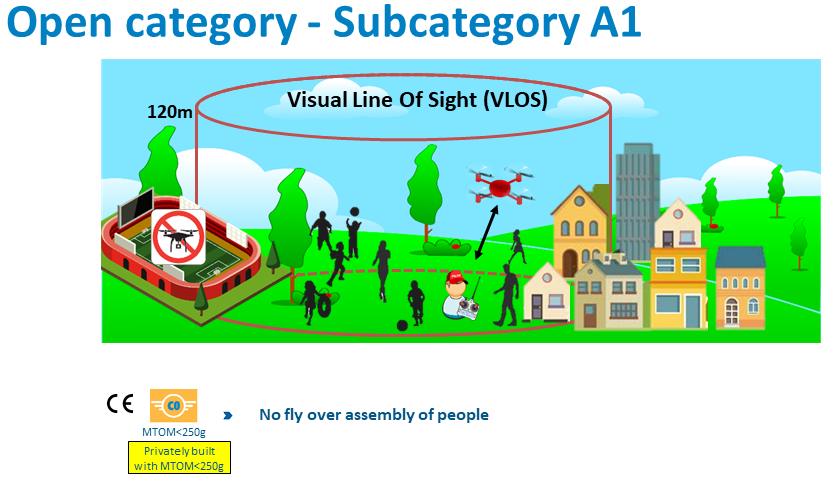

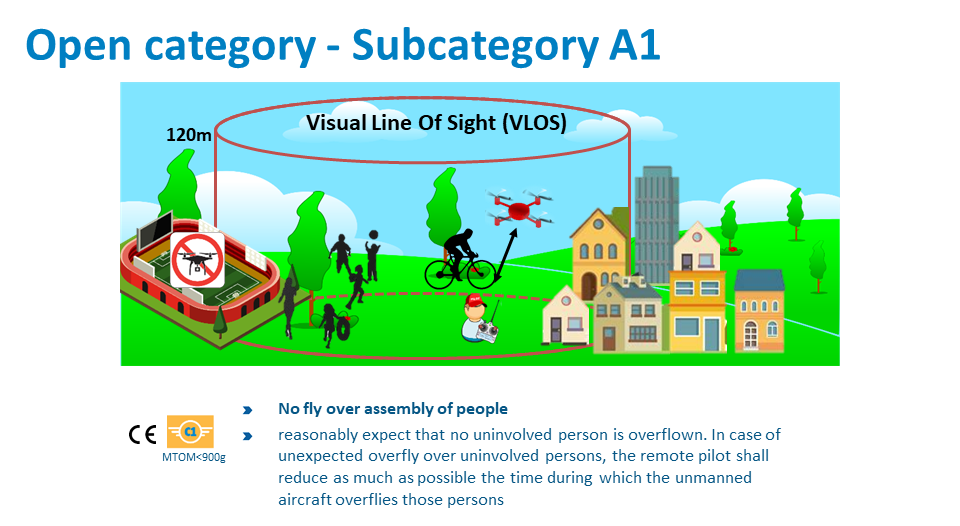

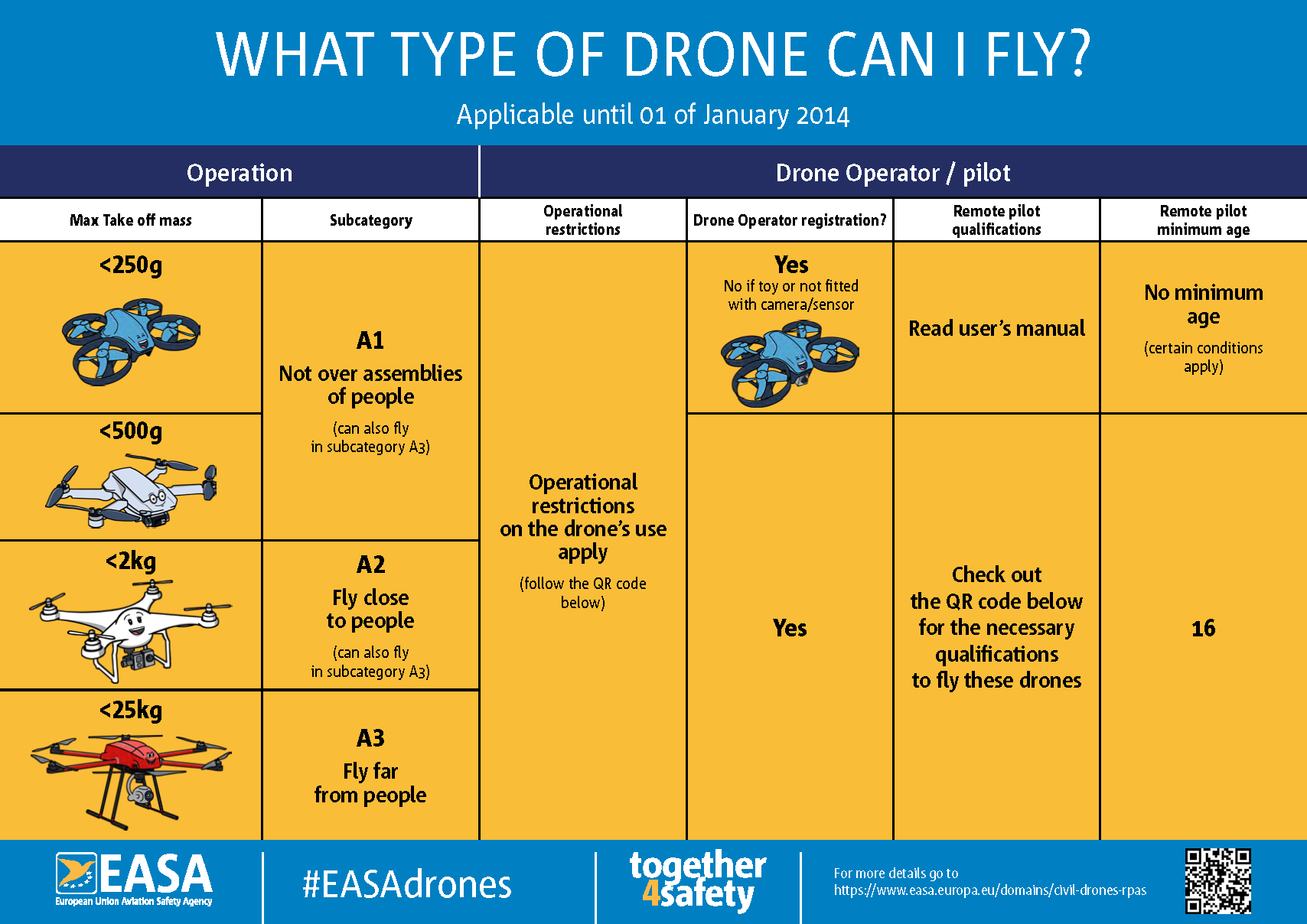

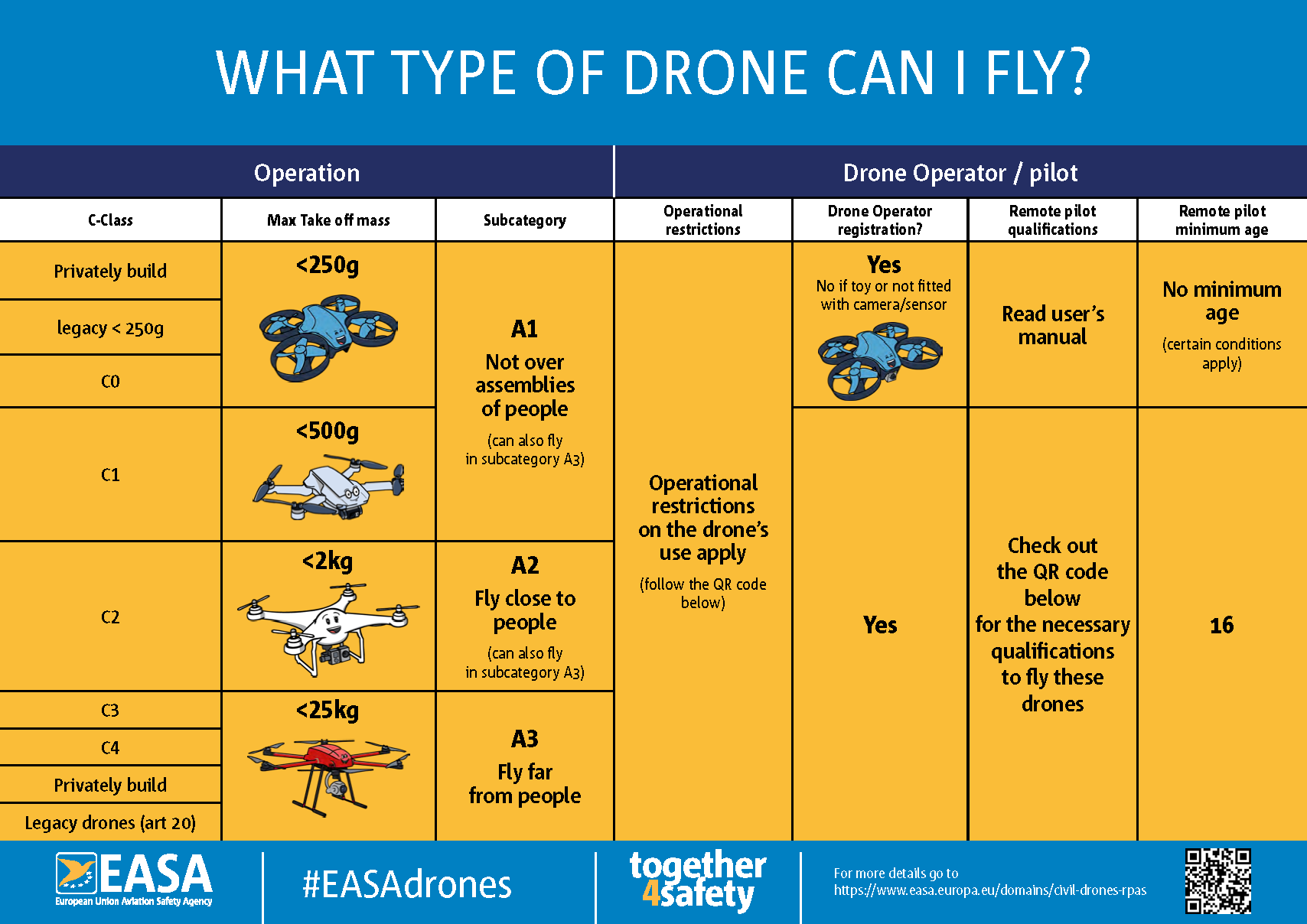

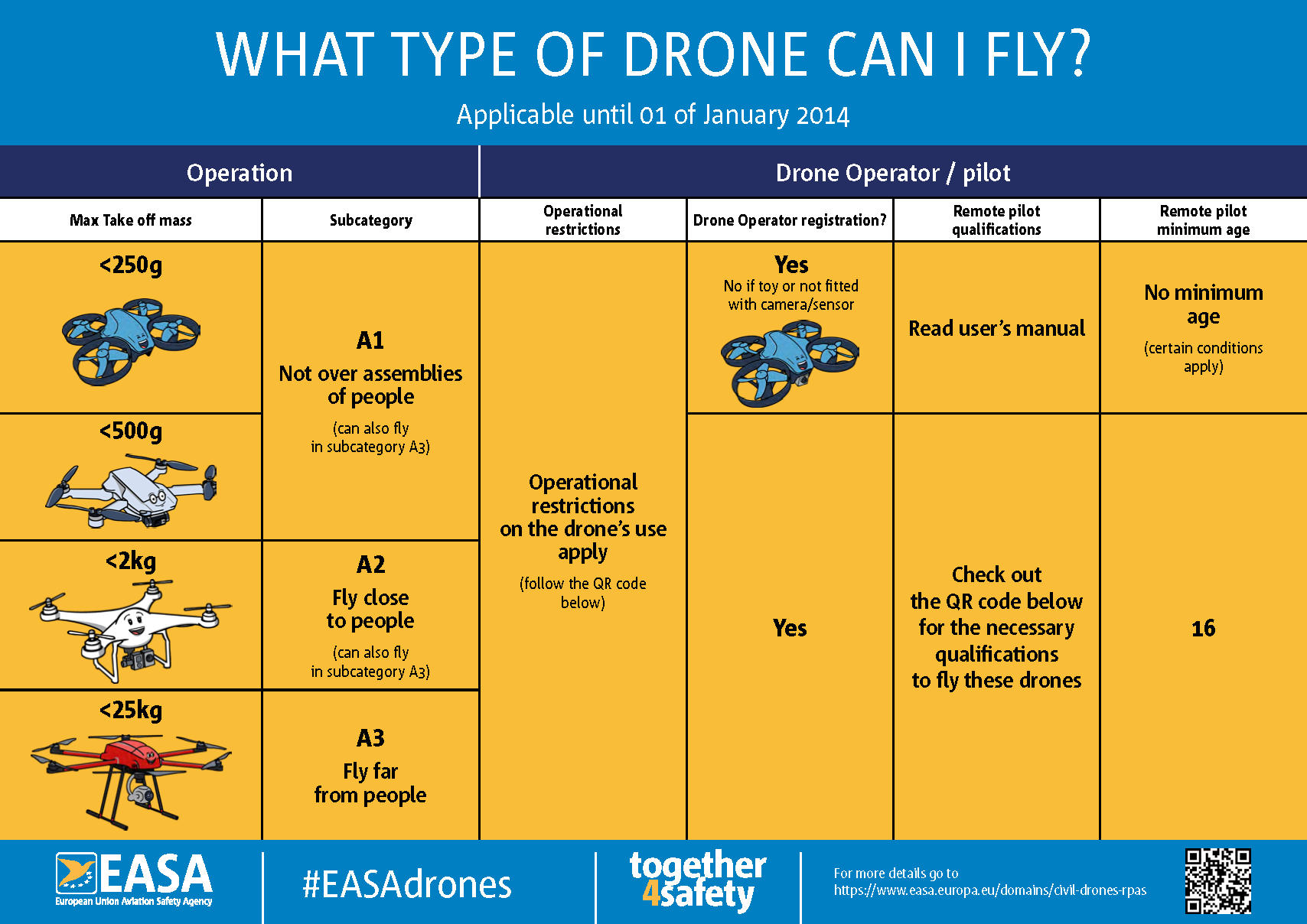

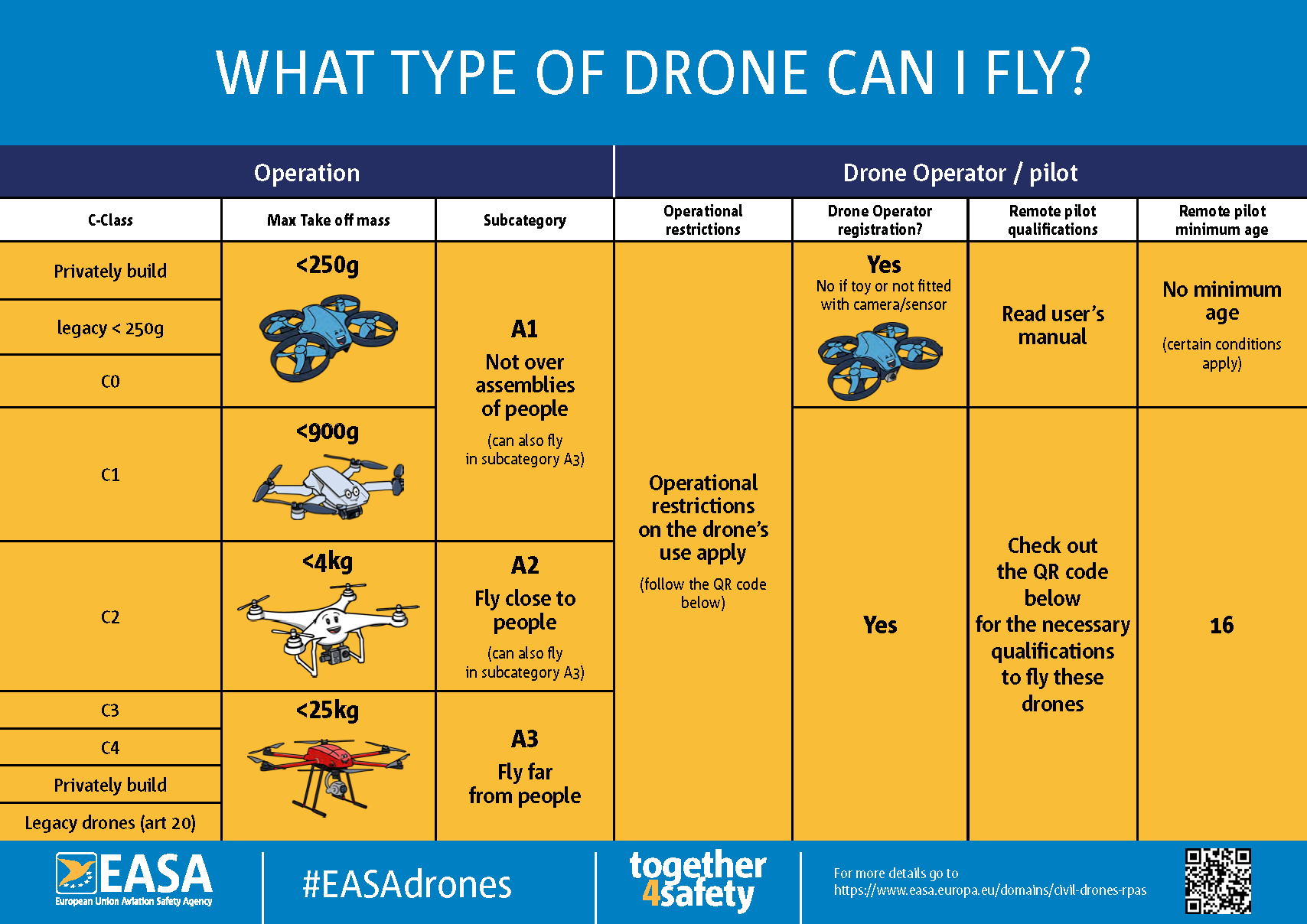

- Understanding the ‘open’ category

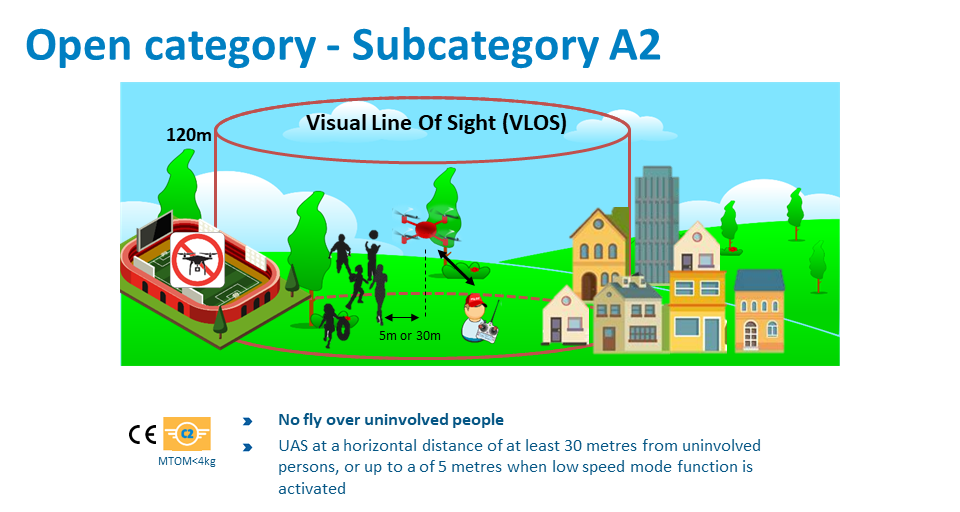

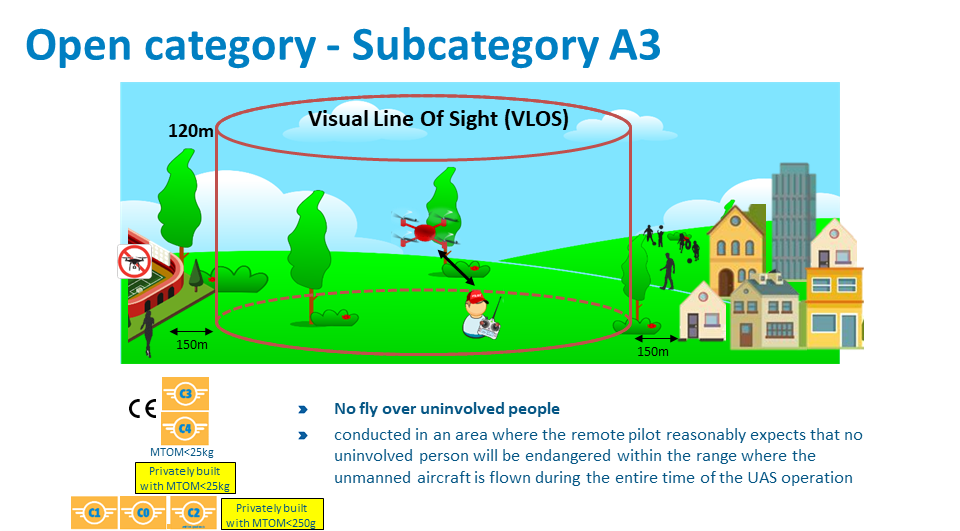

- Requirements under the ‘open’ category

- Training requirements in the 'open' category

- Operational authorisation requirements ‘open’ category

- Responsibilities for drone operators and remote pilots in the ‘open’ category

- Drones without class identification label ’open’ category

- I am into drone racing and/or flying drones with goggles (FPV) ‘open’ category

- I build my own drones (privately built) ‘open’ category

- I plan to provide services (commercial and other) with drones ‘open’ category

- I am a non-EU visitor / drone operator ‘open’ category

- Conduct an Operation in the open category in a state other than the one I am registered

- Specific category

- Understanding the ‘specific’ category

- Training requirements in the ‘specific’ category

- Operational authorisation requirements for the ‘specific’ category

- Responsibilities as a drone operator or remote pilot in the ‘specific’ category

- Drones without class identification label in the ‘specific’ category

- I am into drone racing and/or flying drones with goggles (FPV) ‘specific’ category

- I build my own drones (privately built) ‘specific’ category

- I plan to provide services (commercial and other) with drone(s) ‘specific’ category

- I am a non-EU visitor / drone operator ‘specific’ category

- I would like to know about the light UAS operator certificate (LUC)

- Conduct an Operation in the specific category in a state other than the one I am registered

- Drones with class identification label C0-C6

- Model aircraft

Aircrew

Operational Suitability Data (OSD) for flight crew (FC)

What is the content and purpose of the EASA type rating and licence endorsement lists?

Two separate EASA type rating and licence endorsement lists - flight crew are published by EASA (one for helicopters and one for all other aircraft): Type Ratings and Licence endorsement lists.

These lists constitute the class and type of aircraft categorisations in accordance with definitions of category of aircraft, class of aeroplane, and type of aircraft and paragraph FCL.700 and GM1 FCL.700 of Annex I (Part-FCL) to Commission Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011.

The lists also indicates if operational suitability data (OSD) for flight crew are available. EASA type certificate data sheets (TCDSs) and the list of EASA supplemental type certificates contain further references to OSD. Complete current OSD information is held by the relevant type certificate (TC) or supplemental type certificate (STC) holder.

Furthermore, the lists provide aircraft-specific references relevant to flight crew qualifications and air operations, including references to (non-OSD) documents, such as (J)OEB reports or Operational Evaluation Guidance Material (OE GM).

Explanatory notes for these lists are found at the same website location.

Why do the EASA type rating and licence endorsement lists not contain references to the latest applicable version of an OSD FC document?

The EASA type rating and licence endorsement lists indicate whether an OSD FC document for a relevant aircraft exists. OSD FC documents are certification documents which are held and maintained by TC/STC Holder and are subject to Annex I to Commission Regulation No 748/2012 (Part-21) provisions. Consequently, changes to OSD are handled in accordance with Part-21 procedures in the same way that e.g. changes to aeroplane flight manual (AFM’s) are dealt with. This includes the principle of delegation of privileges to DOAs based on which minor changes to OSD FC are approved under DOA privileges.

The responsibility of tracking the OSD FC document version resides therefore with the TC/STC holder and referencing that in the TR and licence endorsement list could potentially generate inconsistencies.

Users should consider establishing a process to ensure the regular receipt of OSD FC updates, similarly to what might exist for holding current AFM and quick reference handbook (QRH) documents.

Are ODR tables available as part of the operational suitability data (OSD) for flight crew (FC) document?

ODR tables which have been established as part of an OSD FC operational evaluation, are part of the OSD FC data, approved under the type certificate (TC)/ supplemental type certificate (STC) and owned by the TC/STC holder. These ODR tables are original equipment manufacturer OEM generic and must be customized for use by operators to their specific aircraft configurations.

Such ODR tables should therefore be requested directly from the TC/STC holder which has an obligation according to Part-21 to make OSD FC documents available to users.

When should changes to OSD FC provisions be implemented by users to take into account any revised mandatory elements included in a revision?

Article 9a of Commission Regulation No 1178/2011 (amended by Commission Regulation No 70/2014) contains a 2 year transition period for the implementation after initial publication of OSD FC report. This allows training providers, such as ATOs and operators time to adapt their training programmes and provide additional training if needed.

Pilot training courses which were approved before the approval of the OSD FC data should contain the mandatory elements not later than 18 December 2017 or within 2 years after the OSD FC was approved, whichever is later.

Implementation of changes to the OSD FC into existing approved training courses should be implemented within a reasonable timeframe following the OSD change. This timeframe is not clearly defined within the aircrew regulation, however a timeframe of 3 months (or 90 days as under the air ops requirements for an MEL) is considered reasonable.

What is the status of non-mandatory items in the OSD FC? How should users proceed if deviating from non-mandatory items in the OSD FC?

The data contained in OSD FC documents are identified as either ‘mandatory’ or ‘non-mandatory’ elements. While mandatory elements have the status of a rule, non-mandatory elements have the status of Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC).

In order to provide some flexibility to users, non-mandatory elements typically address such items as training devices, training duration, previous experience, or currency. In line with the general principles for AMCs, these elements are non-binding provisions established as a means of compliance with the Aircrew Requirements.

Users may choose Alternative Means of Compliance (AltMoC) to use alternatives to the OSD-FC non-mandatory parts by following the dedicated process for AltMoCs described in the implementing rules for aircrew licensing and air operations. Further details on the AltMoC process can be found on EASA's website.

What aspects should be considered when substituting a training level or device described in the OSD FC by another training level or device?

The data approved in the OSD FC are linked to the minimum training syllabus for a pilot type rating. An evaluation of differences (e.g. for aircraft modifications or between variants) identifies minimum training levels and associated training devices, if required.

With regard to the acquisition of knowledge through theoretical training, some elements may be validated as Level A and can be adequately addressed through self-instruction, whereas other elements may require aided instruction and are identified as Level B. Training organisations may find it more practical to combine Level A and Level B elements into one module of the higher level (such as computer-based training or instructor-led sessions).

With regard to the acquisition of skills through practical training, the OSD FC minimum syllabus identifies elements requiring Level C, D or E practical training and these elements are usually associated in the OSD FC document with specified training devices.

In principle, the devices described in the OSD FC document and the devices used in pilot training should be of the same training level. The use of a more complex device requires additional considerations, regarding the capabilities and characteristics of the device and the impact this may have on the training objective(s).

As an example, the OSD FC may refer to an FMS desktop trainer for Level C training. FMS training in an FTD, an FFS (without motion or vision) or in the aircraft (static, on power) may provide the same training objectives. However, the more complex training environment introduces elements which may affect the focus of the training, the time required, or other factors and these should be taken into consideration.

The same principles apply for the substitution of an FTD. To replicate the characteristics of an FTD Level I with an FTD Level II, to replicate an FTD Level I with an FFS (without motion or vision), or to replicate an FTD Level II with an FFS (without motion or vision) require different considerations to preserve achievement of the training objective.

How can I get access to OSD FC documents?

Contrary to Operational Evaluation Board (OEB) reports which were owned and published by EASA, OSD documents are certification documents which are held by the TC/STC Holder within the framework of Annex I to Commission Regulation No 748/2012 (Part-21).

Paragraph 21.A.62 of Part-21 establishes requirements for the owner of the data (type certificate (TC)/supplemental type certificate (STC) holder) on making these OSD data available. It reads as follows:

21.A.62 Availability of operational suitability data

The holder of the type-certificate or restricted type-certificate shall make available:

(a) at least one set of complete operational suitability data prepared in accordance with the applicable operational suitability certification basis, to all known EU operators of the aircraft, before the operational suitability data must be used by a training organisation or an EU operator; and

(b) any change to the operational suitability data to all known EU operators of the aircraft; and

(c) on request, the relevant data referred to in points (a) and (b) above, to:

1. the competent authority responsible for verifying conformity with one or more elements of this set of operational suitability data; and

2. any person required to comply with one or more elements of this set of operational suitability data.

Consequently, users should request OSD data from the relevant owner, when required.

To assist users in contacting the relevant owner of the document, EASA provides some information on its website for OSD, in particular an OSD contact list based on feedback from manufacturers.

Licensing

What is the difference between the terms FCL (Flight Crew Licensing) and Aircrew?

Aircrew is the common term for "Flight Crew" and "Cabin Crew". Commission Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 laying down technical requirements and administrative procedures related to civil aviation aircrew (“the Aircrew Regulation”) covers both flight crew and cabin crew.

Annex I (Part-FCL) to the Aircrew Regulation contains Implementing Rules for Flight Crew.

Annex V (Part-CC) to the Aircrew Regulation contains Implementing Rules for Cabin Crew.

Following the introduction of a new variant to an existing type rating, how do pilots attain the privileges to operate the new variant?

1. Licensing following the introduction of a new variant to an existing type rating.

Pilots must receive differences training or familiarisation as appropriate in accordance with point FCL.710 of Part-FCL in order to extend their privileges to another variant of aircraft within one class or type rating.

A class or type rating and license endorsement should comply with the class and type ratings that are listed in one of the following EASA publications, as applicable: (1) ‘List of Aeroplanes — Class and Type Ratings and Endorsement List’; and (2) ‘List of Helicopters — Type Ratings List’ .

Unless otherwise required in the EASA Type Rating & License Endorsement List Flight Crew’ published on the Agency’s web page, aircraft models/names of variants which are separated by a horizontal line in the tables require differences training, whereas those aircraft which are contained in the same cell require familiarisation when transitioning from one aircraft to another.

2. Qualification of pilots, instructors and examiners for the new variant:

1. Instructors holding instructor privileges as a TRI or SFI on the existing type intending to use their instructor privileges also on the new variant should complete differences training or familiarization on that new type (as applicable) and qualify in accordance with the last subparagraph of point FCL.910.TRI(b) / point FCL.910.SFI or, alternatively and solely for the initial phase of new aircraft introduction, may obtain a special certificate in accordance with point FCL.900(b) (special conditions for the introduction of a new type).

2. Examiners holding examiner privileges as a TRE or SFE on the existing type intending to use their examiner privileges also on the new variant should qualify in accordance with either FCL.1000(b) (special conditions for the introduction of a new type) or with (1) and (2) above (differences training on the new variant and instructor privileges).

3. Pilots, instructors and examiners without existing type privileges shall complete the full type rating course and follow the requirements of Part-FCL for instructor and examiner privileges on any variant in the type.

How should the new class and type rating list for aeroplanes which is published on the Agency’s website be understood?

For guidance on how to read and understand the EASA List of Class or Type Ratings, please refer to the related Explanatory Notes.

How can a third country (non-EU) licence be converted into a Part-FCL licence?

For conversion of third country licences, the provisions of the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/723 of 4 March 2020 are applicable. That Regulation sets out possible credits and experience requirements, when seeking a Part-FCL licence on the basis of a third-country licence.

National Competent authorities of the EASA Member States are responsible for the conversion of third country licences. Therefore, the national aviation authority of the Member State where an applicant resides or wishes to work should be contacted for further information concerning the applicable acceptance requirements.

To find a list of the national competent authorities (NAAs), please visit the EASA member states page.

To access the different national competent authorities, you should:

1. select the tab ''EASA Member State'';

2. select the MS to be contacted;

3. select the hyperlink to the authority website under the 'Related Content' tab.

To whom can an appeal against the examination/test/check results be sent?

If an applicant does not agree with the result of his/her assessment, he/she can only resolve this problem at the national level.

An applicant cannot apply to the EASA management regarding a decision taken by his/her national aviation authority. Appeals to the Agency can only be made against decisions of the Agency.

Therefore the applicant should resolve this problem on the national level by sending his/her complaints to the national body dealing with complaints against state authorities.

Could the European Central Question Bank be published?

The Agency is the administrator of the European Central Question Bank (ECQB).

Taking into account that:

- Ownership of the copyright of the ECQB database is vested to the European Aviation Safety Agency; and

- Ownership of the contents of the database remains vested to its respective owners; and

- The possession, management and administration of the contents of the database have been fully vested in the hands of the Agency; and

- The contents of the database are confidential and have been treated as such without interruption.

The Agency, acting in the capacity of copyright owner and administrator of the database, enjoys the exclusive right among others, to prevent temporary or permanent reproduction by any means and in any form, as well as to prevent any form of distribution to the public of the database or of copies thereof.

It is the opinion of the Agency that such reproduction and distribution would endanger the functionality and integrity of the applicable examination system and would invalidate the associated substantial investment in both intellectual and monetary terms.

How can a military licence be converted to a civilian one?

The EU rules for recognising military licences can be found in Commission Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 on Aircrew. Article 10 states that the knowledge, experience and skill gained in military service shall be credited towards the relevant requirements of Part-FCL in accordance with the principles of a credit report established by the competent authority of the Member State where a pilot served, in consultation with the Agency.

Therefore, the competent authority of the Member State where the pilot served should be contacted and asked for the provisions applicable for such credits.

Which licence do I have to hold to become a TRI on a multi pilot aeroplane (MPA)?

The prerequisites to obtain and hold any TRI rating are regulated in FCL.915.TRI. There it is stated in a) that an applicant for a TRI rating shall hold a CPL, MPL or ATPL pilot licence on the applicable aircraft category.

Can a co-pilot apply for a TRI rating on a multi pilot aeroplane (MPA)?

Upset Prevention and Recovery Training

Which pilots need to undergo what kind of UPRT?

The different ‘levels’ of UPRT (please refer to the FAQ ‘What is UPRT?’) will be integrated into pilot training as follows:

- basic UPRT

- all modular and integrated CPL and ATP training courses for aeroplanes as well as the integrated MPL training course

- all modular and integrated CPL and ATP training courses for aeroplanes as well as the integrated MPL training course

- ‘advanced UPRT course’

- Part of

- integrated ATP course

- integrated MPL course

- Pre-requisite to

- training courses for single-pilot class or type ratings operated in multi-pilot operations

- training courses for single-pilot high performance complex aeroplanes

- training courses for multi-pilot aeroplanes

- Part of

- class-or type-related UPRT

- training courses for single-pilot high performance complex aeroplanes

- training courses for multi-pilot aeroplanes

- bridge course for extending privileges on a single-pilot aeroplane to multi-pilot operations

To which extent flight simulation training devices (FSTDs) can be used for upset prevention and recovery training (UPRT)?

Training of UPRT exercises within the validated training envelope of the particular FSTD will be possible. In this context, it needs to be highlighted that the revised Part-FCL requirements mandate the conduct of ‘approach-to-stall’ exercises only, with no obligation to conduct ‘post-stall’ exercises. For the conduct of stall or post-stall UPRT exercises, FSTDs need to be qualified in accordance with special evaluation criteria (see Section A, point 18 of Appendix 9 to Part-FCL).

Is UPRT also be mandatory for the LAPL and the PPL?

UPRT, as introduced into Part-FCL with amending Regulation (EU) 2018/1974, is not applicable to LAPL or PPL training.

However, to address the fact that loss of control in-flight is still a major issue in general aviation, the requirements and associated AMC applicable to training flights for revalidation of SEP and TMG class ratings/privileges are planned to be revised to outline the necessity for these training flights to cover emergency procedures (such as different stall scenarios).

What is UPRT?

UPRT stands for aeroplane ‘upset prevention and recovery training’ and constitutes:

• aeroplane upset prevention training: a combination of theoretical knowledge and flying training with the aim of providing flight crew with the required competencies to prevent aeroplane upsets; and

• aeroplane upset recovery training: a combination of theoretical knowledge and flying training with the aim of providing flight crew with the required competencies to recover from aeroplane upsets.

In order to expose pilots to different ‘levels’ of UPRT at various stages of their professional pilot’s career, Annex I (Part-FCL) to Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 contains the following “levels” of UPRT:

• Basic UPRT exercises as part of all CPL and ATP integrated training courses as well as the MPL training course (phase 1 to 3).

• An ‘advanced UPRT course’ including at least 5 hours of theoretical instruction as well as at least 3 hours of dual flight instruction in an aeroplane, with the aim to enhance the student’s resilience to the psychological and physiological aspects associated with upset conditions.

• Class- or type-related UPRT during class or type rating training to address the specificities of the relevant class or type of aeroplane.

Cabin Crew

Definition of ‘cabin crew’

What is the definition of ‘cabin crew member’?

Reference: Commission Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 Aircrew, Article 2 ‘Definitions’.

Article 2 ‘Definitions’ defines ‘cabin crew member’ as follows:

Reference: Commission Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 Aircrew, Article 2 ‘Definitions’.

Article 2 ‘Definitions’ defines ‘cabin crew member’ as follows:

(11) “Cabin crew member” means an appropriately qualified crew member, other than a flight crew or technical crew member, who is assigned by an operator to perform duties related to the safety of passengers and flight during operations;

Does the definition of ‘aircrew’ include cabin crew members?

Reference: Commission Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 Aircrew, Article 2 ‘Definitions’.

Yes, the definition of ‘aircrew’ includes a cabin crew member as well.

Article 2 ‘Definitions’ defines ‘aircrew’ as follows:

(12) “Aircrew” means flight crew and cabin crew;

Medical fitness

Is Cabin Crew Member required to carry his/her medical certificate when on duty?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 Aircrew, Annex IV Part-MED and ED Decision 2011/015/R are available on EASA website.

EU legislation does not contain any provisions on the carriage of a medical report when on duty. MED.C.030(a)(2) requires cabin crew members to provide the related information of their medical report or the copy of their medical report to the operator(s) employing their services. MED.C.030(b) requires the cabin crew medical report to indicate the date of the aero-medical assessment, whether the cabin crew member has been assessed fit or unfit, the date of the next aero-medical assessment and, if applicable, any limitation(s). Any other elements shall be subject to medical confidentiality in accordance with MED.A.015.

Cabin crew members are encouraged to carry their medical report or a copy while on duty to attest their medical fitness and limitation(s). The operator may also have procedures in place through which a cabin crew member’s medical report can be readily available upon request by a competent authority.

Decrease of medical fitness and an ‘unfit’ medical report.

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 Aircrew, Annex IV Part-MED and ED Decision 2011/015/R are available on EASA website.

In case of a decrease in cabin crew member’s medical fitness, the cabin crew member shall, without undue delay, seek the advice of an aero-medical examiner or aero-medical centre or, where allowed by the Member State, an occupational health medical practitioner who will assess the medical fitness of the individual and decide if the cabin crew member is fit to resume his/her duties.

In case a cabin crew member has been assessed as ‘unfit’, the cabin crew member has the right of a secondary review. The cabin crew member shall not perform duties on an aircraft and shall not exercise the privileges of their cabin crew attestation until assessed as ‘fit’ again.

Where can I find the EU medical requirements for Cabin Crew?

References:

Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 Aircrew, Annex IV Part-MED.

ED Decision 2011/015/R containing AMC and GM.

All the referenced regulations are available on EASA website.

NOTE: This FAQ only provides an overview of the area-content covered by the individual Subparts A, C and D of the Reg. 1178/2011. The medical requirements for cabin crew are extensive in text, therefore to find the exact aspect you are looking for, you need to look through the respective Subpart of the Reg. 1178/2011, Annex IV Part-MED and the related AMC and GM (ED Decision 2011/015/R).

Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 - Annex IV - Part-MED: https://www.easa.europa.eu/document-library/regulations/commission-regulation-eu-no-11782011

- Subpart A, Section 1: scope, definitions, decrease in medical fitness, obligations of doctors who conduct aero-medical assessments of cabin crew, etc.

- Subpart C (all): requirements for medical fitness of cabin crew

- Subpart D, Section 1: aero-medical examiners (AEM)

- Subpart D, Section 3: occupational health medical practitioners (OHMP); requirements for doctors who conduct aero-medical assessments of cabin crew

ED Decision 2011/015/R contains acceptable means of compliance (AMC) and guidance material (GM) which complement the rules. The AMC and GM specify the detailed medical conditions and the related medical examinations or investigations: https://www.easa.europa.eu/document-library/agency-decisions/ed-decision-2011015r

Practical ‘raft’ training

Why does Initial training under Part-CC require practical ‘raft’ training even if the operator’s aircraft is not equipped with slide rafts or life rafts?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 Aircrew as amended by Regulation (EU) No 290/2012 Part-CC available on EASA website.

Under EU-OPS, practical training on the use of rafts was required during Initial training. EU-OPS was a regulation directed, and applicable, to operators, therefore, an operator could provide raft training only when a cabin crew member was to actually operate on the operator’s aeroplane fitted with rafts or similar equipment. The training was conducted with that operator’s specific equipment/rafts.

The Initial training under Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011, Part CC is no longer ‘operator-related’, it is generic, therefore, the practical training on rafts or similar equipment and an actual practice in water are not specific to an operator’s equipment.

CCA holders, when recruited by an operator, are expected to have the ability to perform all types of cabin crew duties, including ditching related duties in water. Part-CC Cabin Crew Attestation (CCA) is issued for a life time and is recognised across all EU. Unlike the EU OPS Attestation, the CCA is subject to validity to attest the competence of the individual cabin crew member. This is foreseen in the Basic Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2018/1139) taking into account the increasing mobility of personnel in the aviation industry and the need to harmonise cabin crew qualifications.

An operator may be granted an approval to provide Part-CC Initial training and to issue the CCA (entitled to a mutual recognition as described above). That operator no longer acts as an operator training only its own cabin crew for its specific operations. That operator acts as a training organisation training future cabin crew who, in their life time, may also operate with other operators and in other Member States.

Instructor and Examiner being the same person – conflict of interest

Instructor who provided any topic of the Initial training should not act as Examiner to avoid conflict of interest. What about small operators / cabin crew training organisations employing only one ground Instructor, for example to cover dangerous goods or aero-medical aspects and first aid?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 Aircrew and ED Decision 2012/006/R are available on EASA website.

For any element being examined for the issue of a cabin crew attestation as required in Part CC, the person who delivered the associated training or instruction should not also conduct the examination. However, if the organisation has appropriate procedures in place to avoid conflict of interest regarding the conduct of the examination and/or the results, this restriction need not apply.

Cabin Crew Attestation

My Cabin Crew Attestation was issued in EU Member State A. I would like to join an operator in EU Member State B. Is my Cabin Crew Attestation recognised in EU Member State B?

References:

Regulation (EU) 2018/1139 New Basic Regulation.

Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 Aircrew.

Regulation (EU) No 290/2012 amended by Regulation (EU) No 2015/445 and Regulation (EU) No 245/2014.

All the referenced regulations are available on EASA website.

EU cabin crew member must hold a Cabin Crew Attestation compliant with the rules established by the Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011, as amended by Regulation (EU) No 290/2012, Regulation (EU) No 2015/445 and Regulation (EU) No 245/2014:

https://www.easa.europa.eu/document-library/regulations/commission-regulation-eu-no-11782011

Cabin Crew Attestation issued in one EU Member State, or in EASA Member State, is valid and recognised in all EU Member States without further requirements or evaluation. Each cabin crew member can benefit from a free working movement amongst the EU operators/Member States.

The mutual recognition is established by Regulation (EU) 2018/1139 New Basic Regulation, in Article 67 and Article 3, paragraph (12) and (9).

My cabin crew qualification document was issued in a country that is not a member of the European Union and is not an EASA Member State either. Is my cabin crew qualification document recognised in the European Union?

References:

Regulation (EU) 2018/1139 New Basic Regulation.

Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 Aircrew.

Regulation (EU) No 290/2012 amended by Regulation (EU) No 2015/445 and Regulation (EU) No 245/2014.

All the referenced regulations are available on EASA website.

No, the document is not recognised in the European Union. EU cabin crew member must hold a Cabin Crew Attestation compliant with the rules established by the Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011, as amended by Regulation (EU) No 290/2012, Regulation (EU) No 2015/445 and Regulation (EU) No 245/2014:

https://www.easa.europa.eu/document-library/regulations/commission-regulation-eu-no-11782011

Fire and smoke training

What are the requirements for cabin crew fire/smoke training?

References: (all are available on EASA website)

Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 Aircrew as amended by Regulation (EU) No 290/2012.

Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 Air Operations.

ED Decision 2014/017/R containing AMC and GM to the rules.

NOTE: The requirements on fire and smoke training are extensive in text, therefore to have a better view and understanding, this FAQ should be read together with the rule text. The relevant rule reference is included in each line (type of training) below.

1. Initial training:

- CC.TRA.220 Initial training course and examination

- Appendix 1 to Part-CC Initial training course and examination / Training programme;

Point 8 on Fire and Smoke training

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 290/2012, Annex V Part-CC.

2. Aircraft type training:

- ORO.CC.125 Aircraft type specific and operator conversion training

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 - AMC1 ORO.CC.125(c) and AMC1 ORO.CC.125(d) containing a training programme for aircraft type specific training and operator conversion training respectively

Reference: ED Decision 2014/017/R

3. Recurrent training:

- ORO.CC.140 Recurrent training

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 - AMC1 ORO.CC.140 Recurrent training

Reference: ED Decision 2014/017/R

4. Refresher training:

- ORO.CC.145 Refresher training

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012

What is the content of fire and smoke training during the Initial training ?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 1178/2011 Aircrew as amended by Regulation (EU) No 290/2012, see Annex V ‘Part-CC’ and Appendix I to Part-CC.

Each applicant for a Cabin Crew Attestation shall undergo the Initial training and examination specified in the above referenced regulation. Please, refer to the point 8. Fire and smoke training, which shall cover the following elements:

8.1. emphasis on the responsibility of cabin crew to deal promptly with emergencies involving fire and smoke and, in particular, emphasis on the importance of identifying the actual source of the fire;

8.2. the importance of informing the flight crew immediately, as well as the specific actions necessary for coordination and assistance, when fire or smoke is discovered;

8.3. the necessity for frequent checking of potential fire-risk areas including toilets, and the associated smoke detectors;

8.4. the classification of fires and the appropriate type of extinguishing agents and procedures for particular fire situations;

8.5. the techniques of application of extinguishing agents, the consequences of misapplication, and of use in a confined space including practical training in fire-fighting and in the donning and use of smoke protection equipment used in aviation; and

8.6. the general procedures of ground-based emergency services at aerodromes.

Language proficiency

Is there any requirement on cabin crew member(s) communication with passengers in a certain language?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 Air Operations, Annex III (Part-ORO) and Annex IV (Part-CAT) is available on EASA website.

There is no EU (or ICAO requirement) that cabin crew members must speak English. It is a general practice that cabin crew members do speak English to facilitate the communication in the aviation industry. The operator defines what languages its cabin crew members must be able to speak and at what level.

Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 specifies the following two requirements:

- The operator shall ensure that all personnel are able to understand the language in which those parts of the Operations Manual, which pertain to their duties and responsibilities, are written (ORO.MLR.100(k)), and

- The operator shall ensure that all crew members can communicate with each other in a common language (CAT.GEN.MPA.120).

There is no EU (or ICAO) requirement for a specific language regarding cabin crew communication with passengers. It must be noted that it is difficult, if not impossible, to mandate the ‘required’ languages to be used on board with regard to communication with passengers, as this differs on daily basis from a flight to flight. For example, a German airline has a flight departing from Frankfurt to Madrid and it is assumed that the cabin crew members speak German since they work for a German operator. In addition, they may speak English if the operator selected this language as a criterion. The passenger profile may, however, be such that these languages are not ‘desired’ on this flight as passengers do not necessarily speak or understand any of the two languages (passengers may be e.g. Russian, Chinese, Iranian, Indian, Pakistani, Polish, Finnish, Croatian, Hungarian, Bulgarian, Czech, Slovak, etc., or there is a large group of e.g. Japanese tourists).

Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 mandates the operator to ensure that briefings and demonstrations related to safety are provided to passengers in a form that facilitates the application of the procedures applicable in case of an emergency and that passengers are provided with a safety briefing card on which picture type-instructions indicate the operation of emergency equipment and exits likely to be used by passengers. It is therefore the operator’s responsibility to choose the languages to be used on its flights, which may vary depending on the destination or a known passenger profile. It is also a practice of some operators to employ ‘language speakers’, i.e. cabin crew members speaking certain languages, who mainly operate their language-desired route(s).

Do cabin crew members have to be able to speak English to obtain their Cabin Crew Attestation?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 Air Operations, Annex III (Part-ORO) and Annex IV (Part-CAT) is available on EASA website.

There is no EU (or ICAO requirement) that cabin crew members must speak English. It is a general practice that cabin crew members do speak English to facilitate the communication in the aviation industry. The operator defines what languages its cabin crew members must be able to speak and at what level.

Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 specifies the following two requirements:

- The operator shall ensure that all personnel are able to understand the language in which those parts of the Operations Manual, which pertain to their duties and responsibilities, are written (ORO.MLR.100(k)), and

- The operator shall ensure that all crew members can communicate with each other in a common language (CAT.GEN.MPA.120).

There is no EU (or ICAO) requirement for a specific language regarding cabin crew communication with passengers. It must be noted that it is difficult, if not impossible, to mandate the ‘required’ languages to be used on board with regard to communication with passengers, as this differs on daily basis from a flight to flight. For example, a German airline has a flight departing from Frankfurt to Madrid and it is assumed that the cabin crew members speak German since they work for a German operator. In addition, they may speak English if the operator selected this language as a criterion. The passenger profile may, however, be such that these languages are not ‘desired’ on this flight as passengers do not necessarily speak or understand any of the two languages (passengers may be e.g. Russian, Chinese, Iranian, Indian, Pakistani, Polish, Finnish, Croatian, Hungarian, Bulgarian, Czech, Slovak, etc., or there is a large group of e.g. Japanese tourists).

Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 mandates the operator to ensure that briefings and demonstrations related to safety are provided to passengers in a form that facilitates the application of the procedures applicable in case of an emergency and that passengers are provided with a safety briefing card on which picture type-instructions indicate the operation of emergency equipment and exits likely to be used by passengers. It is therefore the operator’s responsibility to choose the languages to be used on its flights, which may vary depending on the destination or a known passenger profile. It is also a practice of some operators to employ ‘language speakers’, i.e. cabin crew members speaking certain languages, who mainly operate their language-desired route(s).

Aircraft type training

Do I have to undergo Aircraft type specific training and operator conversion training with every new operator I join if I am already qualified on that aircraft type?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 Air Operations, Annex III (Part ORO) is available on EASA website.

Aircraft type specific training and operator conversion training is not transferable from one operator to another as each operator may have its own customised aircraft cabin configurations incl. differences in safety and emergency equipment and standard operating and emergency procedures. Therefore, as required by ORO.CC.125, cabin crew members must complete Aircraft type specific training and operator conversion training before being assigned to operate on the operator’s aircraft.

Can a cabin crew training organisation (CCTO) provide Aircraft type specific training and operator conversion training?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 Air Operations, Annex III (Part ORO) is available on EASA website.

Aircraft type specific training and operator conversion training is a requirement directed to operators as specified in ORO.GEN.005, therefore the operator is responsible for this training. However, an operator may contract out some activities (e.g. training) as specified in ORO.GEN.205 complemented by AMC1 ORO.GEN.205 and GM1 ORO.GEN.205 and GM2 ORO.GEN.205. Therefore, CCTO can only provide Aircraft type specific training and operator conversion training if contracted by an operator to do so. The operator remains responsible for this training and for the competence of its cabin crew.

Reduction of cabin crew during ground operations

Do the evacuation procedures with a reduced number of required cabin crew during ground operations or in unforeseen circumstances require prior endorsement?

Reference: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 Air Operations and the associated ED Decisions are available on EASA website.

The minimum number of cabin crew for an aircraft type, as determined by certification and approved by EASA, is stated on the Type Certification Data Sheet. The minimum number of cabin crew and the evacuation procedures form part of the Operations Manual. Reducing the minimum cabin crew is a deviation from the required minimum number and requires close monitoring. Changes to evacuation procedures with a reduced number of cabin crew are required to be acceptable to the Competent Authority.

The minimum number of cabin crew required in the passenger compartment may be reduced under conditions stated in ORO.CC.205 incl. AMC1 ORO.CC.205 (c)(1). Procedures must be established in the operations manual; it has to be ensured that an equivalent level of safety is achieved with the reduced number of cabin crew, in particular for evacuation of passengers.

Minimum required cabin crew

Determination of the minimum required number of cabin crew on an aircraft

NOTE: The purpose of this FAQ is to explain how the operator and the Competent Authority (National Aviation Authority) conclude the minimum number of cabin crew required on the operator’s aircraft. This FAQ does not provide specific numbers for aircraft types or individual aircraft. The minimum number of cabin crew may vary on each aircraft, depending on the certification history of that aircraft. To learn the minimum number of cabin crew on your aircraft, please, consult your Competent Authority. To have a better view and understanding of the explanation below, this FAQ should be read together with the rule ORO.CC.100 (Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 on air operations).

Minimum number of cabin crew is established during the certification process of the aircraft and this number must be clearly written in the certification documentation (reference: EASA Certification Memorandum CM-CS-008, issued on 03 July 2017). The ‘certification documentation’ is the Type Certificate Data Sheet (TCDS) or the Supplemental Type Certificate (STC).

Therefore, in order to establish the minimum number of cabin crew on the operator’s aircraft, as specified in ORO.CC.100(b)(1) of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012, the operator/National Aviation Authority must check the aircraft certification documentation and apply the number written in the certification documentation.

However, historically, not all aircraft had the number of minimum cabin crew written in the certification documentation, or even established during the certification process. In this case, the operator may use the calculation method specified in ORO.CC.100(b)(2) of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012.

In summary:

Certification documentation of the operator’s aircraft issued:

- Before 3rd July 2017: if the certification documentation does not include the number of minimum cabin crew or the number has not been established for the aircraft, you may apply the calculation method specified in ORO.CC.100(b)(2)).

- After 3rd July 2017: you must apply the number of minimum cabin crew specified in the certification documentation in accordance with the rule ORO.CC.100(b)(1).

Background information:

The development stage of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 (‘AIR OPS’) initially did not include the paragraph (b)(2) in ORO.CC.100, i.e. the ‘1 per 50’ calculation. This inclusion was done last minute and it resulted in the overall lack of clarity of ORO.CC.100(b). To help with the implementation, EASA published Safety Information Bulletin (SIB) 2014-29, which provided detailed information on how to comply with ORO.CC.100. The SIB was supported by the EU Members States, however resulted in a strong opposition by EU operators. As a result, discussions were held in 2015 between EASA and IATA/IACA on the application of ORO.CC.100(b), i.e. how to establish the minimum required number of cabin crew. As an outcome of these discussions, on 7th December 2015 EASA communicated to the stakeholders the ‘EASA conclusions following the consultation on the proposed Certification Memo and Safety Information Bulletin on minimum cabin crew for twin‐aisle aeroplanes’.

On 3rd July 2017, EASA published the above-mentioned Certification Memorandum EASA-CM-CS-008. This document clarifies to aircraft manufacturers and design organisations that the number of cabin crew assumed in their evacuation certification activity must be clearly stated in their documentation. Following the publication of this Certification Memorandum, the TCDSs have been amended to include the minimum number of cabin crew. Some aircraft manufacturers have amended their TCDSs even before the publication of this Certification Memorandum.

There may be cases where the minimum number of cabin crew for the operator’s aircraft will be different (e.g. lower) than the number written in the TCDS. Such a change must be approved by EASA and such an aircraft will hold a Supplemental Type Certificate. STC means that it was demonstrated that the aircraft cabin configuration used by the operator is compliant with the applicable certification specifications with a lower number of cabin crew members than the number specified in the TCDS. If the operator’s aircraft holds a STC, the number of minimum cabin crew written in the STC will be applicable to that aircraft.

Working for multiple operators

I work for Operator A and have short/long-term contract(s) with Operator B. What training do I require when I return back to Operator A after the completion of my short/long-term contract with Operator B?

Ref.: Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 Air Operations, Annex III (Part-ORO) is available on EASA website.

When joining Operator B, the cabin crew member undergoes the Aircraft type specific and operator conversion training & Familiarisation.

When returning to Operator A (after completing the short/long-term contract with Operator B) the options are:

- No training is required, provided the cabin crew member’s recency is within the validity of the Recurrent training and the cabin crew member has operated on Operator A aircraft type during the last 6 months.

- Recurrent training if the validity is about to expire.

- Refresher training, provided the cabin crew member has not operated on Operator A aircraft type for more than 6 months.

- Refresher training, if Operator A considers this training to be necessary due to complex equipment or procedures for the cabin crew member who has been absent from flying duties for less than 6 months.

- Aircraft type specific and operator conversion training & Familiarisation if the validity of the Recurrent training has expired.

What credit can I get as regards Subject 090 Communications for my IR, CPL or ATPL(H)/VFR?

Regulation (EU) 2018/1974 extended the scope of the training & examination on communications for the CPL(A) and CPL(H) (and the ATPL(H)/VFR) from only VFR to both VFR and IFR. Likewise, it extended the scope of communications for the instrument rating from just IFR to both VFR and IFR. Applicants applying for a CPL or ATPL who already hold an IR can be credited towards Subject 090 Communications, if they sat that specific exam. Such credit can also be given to the IR holder who completed ECQB-based exams for Subjects “VFR Communications” and “IFR Communications”. If the applicant only completed “IFR Communications” then no credit for the exam is available. A similar case applies to applicants holding a CPL or ATPL(H)/VFR applying for an IR: credit towards Subject 090 is available, except for where the applicant only holds a pass in “VFR Communications”.

I have successfully passed the CB-IR theoretical knowledge examinations – what instrument rating can I use this for?

According to point FCL.035 to Aircrew Regulation, someone who has successfully passed the IR(A) theoretical knowledge examination (including via the CB-IR(A) route) can use this towards their IR(A), or also for credit towards the Basic IR. If the candidate is seeking to obtain an IR in another aircraft category, additional training at an ATO must be completed.

On which learning objectives will my theoretical knowledge training and exam for the ATPL, CPL or instrument rating be based?

As of 01 February 2022, the theoretical knowledge training and exam is based on learning objectives that include Subject 090 Communications. The learning objectives are published as appendices to AMC1 FCL.310; FCL.515(b); FCL.615(b); FCL.835(d). Further information is available on the ECQB page.

Medical

Where can the aero-medical requirements for ATCOs be found?

The requirements for Air Traffic Controllers’ aero-medical certification can be found in Annex IV –PART ATCO.MED – of the Regulation (EU) 2015/340.

Please follow this link: https://www.easa.europa.eu/regulations#regulations-atco---air-traffic-controllers

Who can perform the Class 1 aero-medical examination?

Initial Class 1 aero-medical examination can be performed only at an Aero-medical centre (AeMC) certified to perform class 1 aero-medical examinations. The aero-medical examination for the renewal or revalidation of the medical certificate can be performed by either an AeMC or an authorized aero-medical examiner (AME) with the privileges to revalidate and renew Class 1 medical certificate. For more details, please refer to the website of the competent authority of a Member State where you are planning to apply. Usually competent authorities publish a list of the authorised AeMCs and AMEs on their website. The list of Member States and the websites of their competent authorities can be found on our website under 'EASA by Country'.

Who can perform the Class 3 aero-medical examination?

Initial Class 3 aero-medical examination can be performed only at an Aero-Medical Centre (AeMC) certified to perform class 3 aero-medical examinations. The recurrent aero-medical examination can be performed by either an AeMC or an authorized aero-medical examiner (AME) with the privileges to revalidate and renew Class 3 medical certificate. For more details, please refer to the website of the competent authority of a Member State where you are planning to apply. Usually competent authorities publish a list of the authorised AeMCs and AMEs on their website. The list of Member States and the web sites of their competent authorities can be found on our website under 'EASA by Country'.

Who can perform the Class 2 and LAPL aero-medical examination?

All Class 2 and LAPL aero-medical examination can be performed by any AeMC or AME authorized to perform aero-medical examinations for aircrew. In addition to that, subject to national provisions, LAPL aero-medical examinations may be performed by General Medical Practitioners (GMPs). For more details, please refer to the website of the competent authority of a Member State where you are planning to apply. Usually competent authorities publish a list of the authorised AeMCs and AMEs including information whether GMPs are allowed to perform aero-medical examinations for LAPL applicants. The list of Member States and the websites of their competent authorities can be found on our website under 'EASA by Country'.

Who can perform the Cabin crew aero-medical assessment?

Cabin Crew aero-medical assessment can be performed by any AeMC or AME authorized to perform aero-medical examinations in accordance with Regulation (EU) 1178/2011. In addition to that, subject to national provisions, aero-medical examinations and assessments may be performed by Occupational Health Medical Practitioners (OHMPs). For more details, please refer to the website of the competent authority of a Member State where you are planning to apply. The list of Member States and the websites of their competent authorities can be found on our website under 'EASA by Country'.

Do you have a list of certified AeMCs and AMEs in Europe?

No, EASA does not have any list of available AeMCs and AMEs. Nevertheless you should be able to find the list of AeMCs and AME on Competent Authorities’ web-sites for each Member State. The list of Member States and links to the competent authorities websites can be found on our website under 'EASA by Country'.

Is there any AeMC available outside Europe?

Where can the aero-medical requirements for Pilots and Cabin Crew be found?

The requirements for Aircrew aero-medical certification can be found in Annex IV – Part-MED – of the Regulation (EU) 1178/2011.

Please follow this link: https://www.easa.europa.eu/regulations#regulations-aircrew

May I exercise the privileges of my PPL licence if I have a Class 1 medical certificate?

Yes, the Class 1 medical certificate includes Class 2 and LAPL privileges.

May I exercise the privileges of my PPL licence if I have a Class 3 medical certificate?

No, the Class 3 medical certificate does not include Class 2 privileges. In order to exercise the privileges of or undertake solo flights for a PPL licence you need to hold a valid Class 2 or Class 1 medical certificate.

If I undertake my aero-medical examination in another Member State than the state that issued my licence do I need to validate resulting medical certificate with my licensing authority?

Flight Simulation Training Devices (FSTDs)

CS- FSTD(A) Issue 2 - UPRT Compliance of current qualified FSTD

In order to satisfy the FCL requirements, of Opinion 6, CS-FSTD(A) Issue 2 is applicable. For updated devices this can be done either through a special evaluation or at the recurrent evaluation (requires application for the Issue 2 elements to be evaluated and credited).

Please refer to CS-FSTD(A) Issue 2 AMC11 FSTD(A).300 Guidance on high angle of attack/stall model evaluation, and approach to stall for previously qualified FSTDs.

When considering the additional requirements under Issue 2 as well for the UPRT requirements please refer to the Explanatory Note to Decision 2018/006/R (reference section 2.5. What are the benefits and drawbacks “Safety improvement by further mitigating/preventing loss of control in-flight (LOC-I). Safety would improve due to the objective testing provisions which would validate not only the cruising configuration, but also the approach and landing configurations. Current FSTDs would be qualified to accurately reproduce the approach to stall in certain conditions and the behaviour of the aeroplane when affected by ice.”

AMC11 applies to previously qualified devices and in some cases where the aeroplane being represented may not have the required validation data – this AMC allows an acceptable means of providing such test data by using a footprint method (when no validation data is available).

If any of the elements of Issue 2 are missing, then this will be shown in the Qualification Certificate as “Restrictions or limitations” to show the users the capabilities of the FSTD.

In conclusion, current qualified FSTD will not need to be fully compliant with CS-FSTD(A) issue 2 but only with the elements related to UPRT and icing. The qualification certificate of the FSTD will therefore show references to two PRDs (Primary Reference Document):

- The PRD used during the initial evaluation of the FSTD;

- CS-FSTD(A) issue 2 for UPRT and icing.

General

Where can I find guidance on the use of ‘shall’, ‘must’, ‘should’ and ‘may’ in the Agency’s rulemaking publications and generally in EU legislation?

This question relates to the English writing standards used in Community legislation. Points 10.23 to 10.32 of the English Style Guide, prepared by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Translation, provide guidance concerning the use of modal verbs in legislation, contracts and the like, as well as an explanation of the distinction between modal verbs used in enacting and non-enacting terms.

Further, points 2.3, 10 and 12 of the Joint Practical Guide of the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission for persons involved in the drafting of European Union legislation also provide guidelines on the principles of drafting Community legislation.

What is the difference between European Community (EC) and European Union (EU) in the regulation reference?

The Lisbon Treaty, the latest primary treaty at EU level, was signed on 13 December 2007 and entered into force on 1 December 2009.

The European Union has been given a single legal personality under this Treaty.

Previously, the European Community and the European Union had different statutes and did not operate the same decision-making rules. The Lisbon Treaty ended this dual system.

On practical terms, all EU legislation has the reference to the EU since 1 December 2009. Up till then, the reference was made to the European Community (EC) as only this body had legal personality.

Why has the numbering of the EU regulations changed as of 2015?

Starting with 2015, the European Union adopts a new numbering system for its legal acts. (see Harmonising the numbering of EU Legal Acts)

What is the definition of an IR, AMC and CS and GM and what differences can be proposed?

Implementing Rules (IR) are binding in their entirety and used to specify a high and uniform level of safety and uniform conformity and compliance. The IRs are adopted by the European Commission in the form of Regulations.

Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) are non-binding. The AMC serves as a means by which the requirements contained in the Basic Regulation, and the IR, can be met. However, applicants may decide to show compliance with the requirements using other means. Both NAAs and organisations may propose alternative means of compliance. ‘Alternative Means of Compliance’ are those that propose an alternative to an existing AMC. Those Alternative Means of Compliance proposals must be accompanied by evidence of their ability to meet the intent of the IR. Use of an existing AMC gives the user the benefit of compliance with the IR.

Certification Specifications (CS) are non-binding technical standards adopted by the EASA to meet the essential requirements of the Basic Regulation. CSs are used to establish the certification basis (CB) as described below. Should an aerodrome operator not meet the recommendation of the CS, they may propose an Equivalent Level of Safety (ELOS) that demonstrates how they meet the intent of the CS. As part of an agreed CB, the CS become binding on an individual basis to the applicant.

Special Conditions (SC) are non-binding special detailed technical specifications determined by the NAA for an aerodrome if the certification specifications established by the EASA are not adequate or are inappropriate to ensure conformity of the aerodrome with the essential requirements of Annex Va to the Basic Regulation. Such inadequacy or inappropriateness may be due to:

- the design features of the aerodrome; or

- where experience in the operation of that or other aerodromes, having similar design features, has shown that safety may be compromised.

SCs, like CSs, become binding on an individual basis to the applicant as part of an agreed CB.

Guidance Material (GM) is non-binding explanatory and interpretation material on how to achieve the requirements contained in the Basic Regulation, the IRs, the AMCs and the CSs. It contains information, including examples, to assist the user in the interpretation and application of the Basic Regulation, its IRs, AMCs and the CSs.

Implementing Rules are available in all of the national languages of the EASA Member States. How is the quality of these translations assured? Who is responsible for the translations?

EASA is committed to facilitating the production of good quality translations. To ensure this and, where necessary, to improve, EASA has set up a Translation Working Group in 2008. This Working Group is made up of members of the National Aviation Authorities (NAAs), the Translation Centre of the EU Bodies (CdT), as well as EASA staff members. Also, EASA in cooperation with NAAs and CdT, is developing glossaries in the different aviation domains, such as Air Operations or Air Traffic Management, to enhance the quality of translations. The Member States also contribute to this project in order to capitalise on existing material and experience.

The final responsibility for translations lies with the EU Commission. The correction of translation mistakes of the Implementing Rules follows the same formal procedure as for their adoption: 1. preparation of the proposal, 2. interservice consultation, 3. committee, 4. scrutiny of European Parliament and of European Council, and 5. adoption. For minor mistakes, the procedure may be shorter. In any case, the linguistic changes will have to be agreed by the Commission’s translation services. These linguistic services will check that no substantial change is introduced, that the term used is acceptable according to an internal translation code or that the same change is included in all linguistic versions.

What is the progress of a regulation towards publication?

The Agency drafts regulatory material as Implementing Rules, Acceptable Means of Compliance, Guidance Material and Certification Specifications. These are available for consultation (as Terms of Reference, Notices of Proposed Amendment and Comment Response Documents). After consultation, the Implementing Rules are sent to the European Commission as Opinions.

Following publication of the Opinions, responsibility for completing the decision-making process prior to the Regulation’s publication in the Official Journal of the European Union passes onto the European Commission. The Opinions’ progress can be followed via the European Commission’s comitology website. It is advisable to search by year and for the committee dealing with these Opinions: Committee for the application of common safety rules in the field of civil aviation. As several Opinions may be negotiated in one such committee meeting, it is difficult to search by rule or title.

Once the committee has adopted the draft regulation, it is passed on to the European Parliament and Council for scrutiny. Further information and links to the documents under scrutiny can be found via the European Parliament’s Register of Documents.

The Agency is responsible for finalising the associated Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC), Guidance Material (GM) and Certification Specifications. As these need to take into account any changes made to the Cover Regulation and Implementing Rules by the EASA Committee, European Parliament and Council, the Decisions are published on the Agency website shortly after the date when their corresponding regulation has been published in the Official Journal.

The Agency also publishes a rulemaking programme, listing the tasks that are ongoing and advance planning. It is available here.

What is the legal status of documents published during the EASA Rulemaking process such as Notice of Proposed Amendment (NPA), Comment Response Document (CRD) or an Opinion? Can they be used if there is no EU rule available?

The proposed draft rules published during the EASA Rulemaking process are not binding documents as they are still subject to change. This may occur either during the EASA rulemaking process or through the Commission's comitology process. Consequently, NPAs, CRDs and Opinions cannot be used in place of an EU rule.

NPAs and CRDs are part of the Agency's rulemaking process, at different stages. They inform and consult stakeholders on possible rule changes or new rules. The NPAs include an explanatory note, the proposed draft rules, a regulatory impact assessment (RIA) — if applicable, and proposed actions to support implementation. They are published on the Agency’s website to allow any person or organisation with an interest in or being affected by the draft proposed rule to submit their comments.

The CRD to a particular NPA is published after the comments have been reviewed and contains a summary of the comments received, along with all the comments submitted by stakeholders on that particular NPA and EASA’s responses to those comments.

Most of the times, the EASA rulemaking process also leads to the issuance of Opinions, which contain proposals of implementing and delegated acts. They are submitted to the European Commission, as a proposal to change existing regulations or create new ones.

More information on EASA rulemaking.

What is the comitology procedure?

Please refer to the information provided by the European Commission at:

https://ec.europa.eu/info/implementing-and-delegated-acts/comitology_en

What does 'Cover’ Regulation mean?

Implementing rules are Commission regulations. A regulation is usually composed of a short introductory regulation, colloquially known as ‘cover regulation’, and Annexes thereto, containing the technical requirements for implementation. In the EASA system, these Annexes are usually called Parts (e.g. Part-21 is an annex to Regulation 1702/2003; Part-ORO is an annex to Regulation (EU) No 965/2012).

The ‘cover’ regulation is usually short (a few pages) and it includes:

- The preamble made up of:

- Citations (the paragraphs introduced by ‘Having regard to…’); and

- Recitals (clauses introduced by ‘whereas’), explaining the reasons for the contents of the enacting terms (i.e. the articles) of an act, the background principles and considerations that lead the legislator to adopt the regulation;

- The articles of the regulation, which contain:

- A description of the objective and scope of the regulation;

- Definitions that are used throughout the regulation and its annexes;

- The establishment of the applicability of its annex(es);

- Conversion and transition measures.

Can the information provided in EASA's FAQ be considered legally binding?

No, the information included in the Agency’s FAQs cannot be considered in any way to be legally binding. EASA is not the competent authority to interpret EU Law. Such responsibility rests with the judicial system, and ultimately with the Court of Justice of the European Union. Therefore any information included in these FAQs shall only be considered as EASA's technical understanding on a specific matter.

Continuing Airworthiness

In case the answer you were looking for in this FAQ section is not available, you are invited to contact first your competent authority (here for EASA member states). For further assistance, you might submit your enquiry, together with the description of your authority’s position, here.

COVID-19 - Continuing Airworthiness

What is the flexibility allowed to the person or organisation responsible for the aircraft continuing airworthiness when it comes to the planning of Aircraft Maintenance Programme (AMP) scheduled maintenance tasks with intervals expressed in calendar time?

1. Purpose of the document

The Agency was requested by the industry for additional guidance on the application of the airworthiness rules in respect to certain specific issues particularly affected by the current COVID-19 crisis. One of those topics concerns the obligations of the person or organisation responsible for continuing airworthiness of aircraft when it comes to the accomplishment of Aircraft Maintenance Programme tasks with intervals expressed in calendar times. Accordingly, the Agency prepared this additional, temporary, guidance, which complements the existing AMC/GM to Commission Regulation (EU) No 1321/2014.

The guidance provided in this document is primarily intended for ‘Part-M’ aircraft, but can be used also as regards ‘Part-ML’ aircraft, except that in case of ‘Part-ML’ aircraft, the competent authority does not need to be involved if an AMP task is to be postponed, as this is done under the responsibility of the aircraft owner or the organisation responsible for the aircraft continuing airworthiness. This person or organisation may also decide, if necessary to revise the AMP, which will not involve the competent authority.

2. Description of the issue

During the COVID-19 crisis, a large number of aircraft is being parked / stored at different and partially remote locations. This guidance document was prepared based on an assumption that these aircraft have been subject to parking/storage procedures defined by the Type Certificate (TC) Holder (those parking and storage procedures are usually contained in a chapter of the Aircraft Maintenance Manual (AMM e.g. Chapter 10). If the existing AMM does not contain parking/storage procedures, the TC Holder should be contacted.

Note: It is not necessary to revise the AMP to include the parking/storage tasks to be followed.

During the COVID-19 crisis, the parked/stored aircraft are not operated and consequently the AMP scheduled maintenance tasks based on ‘Flight hours’ and ‘Flight cycles’ are not impacted. On the other hand the AMP scheduled maintenance tasks based on intervals (and threshold, if applicable) expressed in calendar times need to be considered. Indeed, some of the calendar time based scheduled maintenance tasks will become due during parking/storage period.

In the normal practice, following the principles of AMC M.A.301(c) and point 4 of Appendix I to AMC M.A.302 and AMC M.B.301(b), if a scheduled maintenance task cannot be performed within the interval approved in the AMP, its postponement may be allowed in accordance with pre-defined ‘permitted variation’ agreed with the CA in the AMP.

3. Considerations in the frame of COVID-19 crisis

3.1 Postponement until the end of parking/storage period

In the current situation, it may not be always feasible, to perform the calendar scheduled maintenance tasks of the AMP in due time, or within the permitted variation specified in the AMP.

In such cases, it is acceptable for EASA to plan the accomplishment of these tasks (even if they have become due multiple times during the parking/storage period) at the next suitable opportunity (e.g. next weekly check of storage/parking procedure), or at the end of the storage/parking period, but in any case before the next flight, as part of the work package necessary for the de-preserving/de-storage of the aircraft.

Note: Certain AMP scheduled maintenance tasks may be assessed as unnecessary because they are covered by equivalent tasks in the parking/storage procedures put in place.

3.2 Postponement beyond return to service

If exceptionally, a calendar task needs to be postponed until after the return to service and beyond the AMP permitted variation, the aircraft owner or CAMO/CAO should receive advice from the TCH or the Design Approval holder (DAH) on such postponement and on the subsequent due date after the accomplishment.

The applicant should then submit such postponement, together with the proposed technical justification, including if appropriate, a risk assessment, for approval by the CA.

The CA should consider the following conditions, mitigating actions or any other elements which the CA deems necessary, when allowing a postponement of a due calendar task after return to service:

- An approved maintenance organisation has applied the appropriate parking/storage procedures during the full period.

- The owner/CAMO/CAO has monitored what AMP tasks are due (M.A.708(b)(4), CAMO.A.315(b)(5) and CAO.A.075(b)(7)).

- This does not apply to mandatory continuing airworthiness instructions (MCAI) such as AD or ALS tasks.

- The environmental conditions where the aircraft was parked/stored have been taken into consideration. Certain calendar tasks may be more relevant to a particular storage environment, e.g. wet, salty conditions propagate corrosion.

In addition, the importance of the AMP task (e.g. based on MRB task type/source/category, reliability-alert task), the performance of the CAMO/CAO quality system, and if applicable the review of the risk assessment performed by the applicant, should also be considered.

Based on the above elements, it may be possible to allow an exceptional (one-off) postponement, not exceeding the following:

(i) AMP task interval of 1 year or less: up to 3 months

(ii) AMP task interval of more than 1 year, but not exceeding 2 years: up to 4 months

(iii) AMP task interval of more than 2 year, but not exceeding 3 years: up to 5 months

(iv) AMP task interval of more than 3 years: up to 6 months.

Such postponement should be calculated from the original AMP task due date, unless otherwise agreed with the competent authority.

The subsequent due date should also be part of the CA approval.

The Aircraft continuing airworthiness record system, and if applicable, the aircraft technical log system should properly record such agreement and the effective accomplishment date.

Depending on the length of the COVID-19 crisis and the future annual utilisation of the aircraft, the CA may also require to the owner/CAMO/CAO an ad-hoc review of the AMP pursuant to M.A.302(h).

Under the present rules, is the person responsible for the continuing airworthiness of an aircraft (owner, CAO or CAMO) allowed to split the customised maintenance checks?

1. Purpose of the document

The Agency was requested by the industry for additional guidance on the application of the airworthiness rules in respect to certain specific issues particularly affected by the current COVID-19 crisis. One of those topics concerns the possibility for a person responsible for continuing airworthiness of aircraft to split the customised maintenance tasks. Accordingly, the Agency prepared this additional, temporary, guidance document, which complements the existing GM/AMC to Commission Regulation (EU) No 1321/2014.

2. Description of the issue

Considering the large number of aircraft grounded at the same time during the COVID-19 crisis, the movement restrictions of persons, the temporary lack of access to certain facilities and/or services, the competent authorities may need to facilitate a more practical scheduling process of the Aircraft Maintenance Programme (AMP) tasks and a simpler process of approving changes to the responsible organisation’s procedures, in order to ensure as much as possible the continuation of organisation activities during this period, in compliance with the applicable requirements.

For aircraft managed under Annex I (Part-M) to Commission Regulation (EU) No 1321/2014, in accordance with M.A.301(c), the owner, CAO or CAMO, as applicable, should have a system to ensure that all aircraft maintenance tasks are performed within the limits prescribed by the approved Aircraft Maintenance Programme (AMP) and that, whenever a maintenance task cannot be performed within the required time limit, its postponement is allowed in accordance with a procedure agreed by the competent authority (CA).

If an owner, CAO or CAMO, as applicable, has developed the AMP through grouping of individual maintenance tasks into packages based on usage parameter(s) (e.g.: annual inspection, 1,000 FH inspection) or letter-checks (e.g.: A-check, C1-check), as per points M.A.302(a)&(f) any split of such a package back to individual maintenance tasks requires an amendment to the AMP and is subject to direct approval by the CA as per point M.A.302(b), unless this is already covered by the indirect approval of the AMP as per point M.A.302(c).

Under the COVID-19 circumstances, splitting the maintenance packages may give to the aircraft owner, CAO or CAMO, as applicable, the possibility to tailor and schedule the individual maintenance tasks as they are strictly needed, fitting the aircraft operational needs and activities, as well as the availability of the required facilities and/or services. It must be ensured that the AMP task intervals are respected.